Reposted from the Physics Virtual Bookshelf.

David M. Harrison

Here is a favorite statement of Bohr’s Principle of Complementarity, based on so-called wave-particle duality for light:

“But what is light really? Is it a wave or a shower of photons? There seems no likelihood for forming a consistent description of the phenomena of light by a choice of only one of the two languages. It seems as though we must use sometimes the one theory and sometimes the other, while at times we may use either. We are faced with a new kind of difficulty. We have two contradictory pictures of reality; separately neither of them fully explains the phenomena of light, but together they do.”—Albert Einstein and Leopold Infeld, The Evolution of Physics, pg. 262-263.

Incidentally, I have been told that Infeld wrote the entire book The Evolution of Physics in 1938, but was experiencing difficulty in getting anyone to publish it. Once Einstein put his name on it, all such difficulties disappeared.

John Wheeler, with his usual insight and striking prose, neatly summarises the status of the principle:

“Bohr’s principle of complementarity is the most revolutionary scientific concept of this century and the heart of his fifty-year search for the full significance of the quantum idea.”—Physics Today 16, (Jan 1963), pg. 30.

A nice analogy is Figure-Ground studies such as the one shown to the right. Looked at one way, it is a drawing of a vase; looked at another way it is two faces.

A nice analogy is Figure-Ground studies such as the one shown to the right. Looked at one way, it is a drawing of a vase; looked at another way it is two faces.

We can switch back and forth between the two viewpoints. But we can not see both at once. But the figure is both at once.

Similarly, we can think of an electron as a wave or we can think of an electron as a particle, but we can not think of it as both at once. But in some sense the electron is both at once. Being able to think of these two viewpoints at once is in some sense being able to understand Quantum Mechanics.

I do not believe that Quantum Mechanics is understandable, at least for the usual meaning of the word understand.

Thus when we think of an electron in a Hydrogen atom, we can imagine it as a particle in orbit around the central proton. We can also imagine it as the wave function, its wave aspect; it turns out that the wave function for the electron in the Hydrogen atom is spherically symmetric with maximum density at the center of the atom.

A Flash animation of these two viewpoints of an electron in a Hydrogen atom may be accessed by clicking on the red button to the right. It will appear in a separate window, and has a file size of 9.6k In order to view it, you need to have the Flash player of Version 5 or later installed on your computer; the Flash player is available free.

We can illustrate the Principle of Complementarity with some examples by Bohr himself:

- “The opposite of a true statement is a false statement, but the opposite of a profound truth is usually another profound truth.”

- Life: a form through which matter streams.

Life: a collection of matter. - Justice and love.

References to the above examples are: 1) Ken Wilbur, Spectrum of Consciousness, pg. 34. 2)Heisenberg, Physics and Beyond, pg. 105. 3)From the Chinese Taoist text I Ching, as reported in Reference 2, pg. 15.

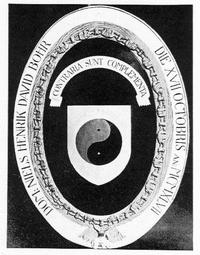

In 1947 Bohr was awarded the Order of the Elephant from the Danish government. For a proud Dane like Bohr, this was a very big deal, and Bohr is the only person to be awarded it who was not royalty and/or a famous general. As part of the award, the winner’s family coat of arms is carved into a sort of wall of fame. Bohr’s family, though, did not have a coat of arms, so Bohr got to design one himself. The figure to the right is what he designed.

In 1947 Bohr was awarded the Order of the Elephant from the Danish government. For a proud Dane like Bohr, this was a very big deal, and Bohr is the only person to be awarded it who was not royalty and/or a famous general. As part of the award, the winner’s family coat of arms is carved into a sort of wall of fame. Bohr’s family, though, did not have a coat of arms, so Bohr got to design one himself. The figure to the right is what he designed.

You will notice that he choose the ancient Chinese symbol for the Tao, the “Yin-Yang Symbol,” for the centerpiece. He did not do this lightly. The inscription reads CONTRARI SUNT COMPLEMENTA or Opposites Are Complements. Thus he chose to represent his Principle of Complementarity as the centrepiece of his coat of arms.

As you probably know, in Taoist philosophy all is related to pairs of opposites which are called Yang and Yin. The table below illustrates. All the entries but the last are as given by the traditional Taoist classification.

| Yang | Yin |

|---|---|

| Sunny | Shady |

| Masculine | Feminine |

| Active | Passive |

| Rational | Intuitive |

| Heavy | Light |

| Particle | Wave |

The last entry in the above table is by the author of this document. You may wish to muse about whether I have got the right label in the correct column.

Similarly, the first two of the following quotations are famous to Taoists, while the last is not nearly as well-known:

-

“The ten thousand things carry yin and embrace yang.

They achieve harmony by combining these forces.”

— Lao Tsu, Tao Te Ching 42

- “The Tao that can be told is not the true Tao.”

— Tao Te Ching 1

- “The electron that can be told is not the true electron.”

— David Harrison

At the risk of pushing the illustration of Western physics by means of Eastern ideas too far, you may wish to consider the following:

“[In 1961] I had occasion to discuss Bohr’s ideas with the great Japanese physicist [Yukawa], whose conception of the meson with its complementary aspects of elementary particle and field of nuclear force is one of the most striking illustrations of the fruitfulness of the new way of looking at things that we owe to Neils Bohr. I asked Yukawa whether the Japanese physicists had the same difficulty as their Western colleagues in assimilating the idea of complementarity … He answered ‘No, Bohr’s argumentation has always appeared quite evident to us; … you see, we in Japan have not been corrupted by Aristotle.” — Rosenfeld, Physics Today 16, (Oct 1963), pg. 47.

Finally, we close this section by considering the methodology used by Bohr, as well as many other creative geniuses both in and out of the sciences: paradox.

“Among all paradigms for probing a puzzle, physics proffers none with more promise than a paradox … No one took the paradox [of quantum theory] more seriously than Bohr. No one worked around the central mystery with more energy wherever work was possible. No one brought to bear a more judicious combination of daring and conservativeness, nor a deeper feel for the harmony of physics.” — Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler, Gravitation pg. 1197

“The Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory starts from a paradox.” Heisenberg, Physics and Philosophy, pg. 44

Similarly, in the Eastern traditions understanding is often achieved through deep consideration of paradox. A well-known example is the koans used in the Zen tradition. A famous koan is “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” There are more-or-less unique correct answers to the koans, which can be found by deep internal questioning.