system, doesn't charge for long-distance service. And unlike most commercial

computer networks, it doesn't charge for access time, either. In fact the

Internet itself, which doesn't even officially exist as an entity, never charges

for anything. Each group of people accessing the Internet is responsible for

their own machine and their own section of line.

certain deep and basic sense. It's rather like the anarchy of the English

language. Nobody rents English, and nobody owns English. As an English-

speaking person, it's up to you to learn how to speak English properly and

make whatever use you please of it (though the government provides certain

subsidies to help you learn to read and write a bit). Otherwise, everybody just

sort of pitches in, and somehow the thing evolves on its own, and somehow

turns out workable. And interesting. Fascinating, even. Though a lot of people

earn their living from using and exploiting and teaching English, English as an

institution is public property, a public good. Much the same goes for the

Internet. Would English be improved if the

“The English Language, Inc. had a board of directors and a chief executive

officer, or a President and a Congress? There'd probably be a lot fewer new

words in English, and a lot fewer new ideas.

It's an institution that resists institutionalization. The Internet belongs to

everyone and no one.

Internet put on a sounder financial footing. Government people want the

Internet more fully regulated. Academics want it dedicated exclusively to

scholarly research. Military people want it spy-proof and secure. And so on

and so on.

TrustMark 2001 by Timothy Wilken

Internet, so far, remains in a thrivingly anarchical condition. Once upon a

time, the NSFnet's high-speed, high-capacity lines were known as the Internet

Backbone, and their owners could rather lord it over the rest of the Internet;

but today there are backbones in Canada, Japan, and Europe, and even

privately owned commercial Internet backbones specially created for carrying

business traffic. Today, even privately owned desktop computers can become

Internet nodes. You can carry one under your arm. Soon, perhaps, on your

wrist.

discussion groups, long-distance computing, and file transfers.

than the US Mail, which is scornfully known by Internet regulars as snailmail.

Internet mail is somewhat like fax. It's electronic text. But you don't have to

pay for it (at least not directly), and it's global in scope. E-mail can also send

software and certain forms of compressed digital imagery. New forms of mail

are in the works.

of news, debate and argument is generally known as USENET. USENET is, in

point of fact, quite different from the Internet. USENET is rather like an

enormous billowing crowd of gossipy, news-hungry people, wandering in and

through the Internet on their way to various private backyard barbecues.

USENET is not so much a physical network as a set of social conventions. In

any case, at the moment there are some 2,500 separate newsgroups on

USENET, and their discussions generate about 7 million words of typed

commentary every single day. Naturally there is a vast amount of talk about

computers on USENET, but the variety of subjects discussed is enormous, and

it's growing larger all the time. USENET also distributes various free

electronic journals and publications.

TrustMark 2001 by Timothy Wilken

speed core of the Internet itself. News and e-mail are easily available over

common phone-lines, from Internet fringe- realms like BITnet, UUCP and

Fidonet. The last two Internet services, long-distance computing and file

transfer, require what is known as direct Internet access – using TCP/IP.

still a very useful service, at least for some. Programmers can maintain

accounts on distant, powerful computers, run programs there or write their

own. Scientists can make use of powerful supercomputers a continent away.

Libraries offer their electronic card catalogs for free search. Enormous CD-

ROM catalogs are increasingly available through this service. And there are

fantastic amounts of free software available.

programs or text. Many Internet computers – some two thousand of them, so

far – allow any person to access them anonymously, and to simply copy their

public files, free of charge. This is no small deal, since entire books can be

transferred through direct Internet access in a matter of minutes. Today, in

1992, there are over a million such public files available to anyone who asks

for them (and many more millions of files are available to people with

accounts). Internet file-transfers are becoming a new form of publishing, in

which the reader simply electronically copies the work on demand, in any

quantity he or she wants, for free. New Internet programs, such as archie,

gopher, and WAIS, have been developed to catalog and explore these

enormous archives of material.

Any computer of sufficient power is a potential spore for the Internet, and

today such computers sell for less than $2,000 and are in the hands of people

all over the world. ARPA's network, designed to assure control of a ravaged

society after a nuclear holocaust, has been superceded by its mutant child the

Internet, which is thoroughly out of control, and spreading exponentially

through the post-Cold War electronic global village. The spread of the

TrustMark 2001 by Timothy Wilken

though it is even faster and perhaps more important. More important,

perhaps, because it may give those personal computers a means of cheap, easy

storage and access that is truly planetary in scale.

Commercialization of the Internet is a very hot topic today, with every

manner of wild new commercial information- service promised. The federal

government, pleased with an unsought success, is also still very much in the

act. NREN, the National Research and Education Network, was approved by

the US Congress in fall 1991, as a five-year, $2 billion project to upgrade the

Internet backbone. NREN will be some fifty times faster than the fastest

network available today, allowing the electronic transfer of the entire

Encyclopedia Britannica in one hot second. Computer networks worldwide

will feature 3-D animated graphics, radio and cellular phone-links to portable

computers, as well as fax, voice, and high- definition television. A multimedia

global circus!

little resemblance to today's plans. Planning has never seemed to have much to

do with the seething, fungal development of the Internet. After all, today's

Internet bears little resemblance to those original grim plans for RAND's

post- holocaust command grid. It's a fine and happy irony.

and a modem, get one. Your computer can act as a terminal, and you can use

an ordinary telephone line to connect to an Internet-linked machine. These

slower and simpler adjuncts to the Internet can provide you with the netnews

discussion groups and your own e-mail address. These are services worth

having – though if you only have mail and news, you're not actually on the

Internet proper.

TrustMark 2001 by Timothy Wilken

campus machine, and you may be able to get those hot-dog long-distance

computing and file-transfer functions. Some cities, such as Cleveland, supply

freenet community access. Businesses increasingly have Internet access, and

are willing to sell it to subscribers. The standard fee is about $40 a month –

about the same as TV cable service.

cheaper and easier. Its ease of use will also improve, which is fine news, for

the savage UNIX interface of TCP/IP leaves plenty of room for advancements

in user-friendliness. Learning the Internet now, or at least learning about it, is

wise. By the turn of the century, network literacy, like computer literacy

before it, will be forcing itself into the very texture of your life.”1

contractors.

were believed to have some sort of access to the Internet.

57,037,000, and that there were 320 million web pages.

holiday season was $8.2 billion.

Internet. The growth rate of the internet is in excess of 10 percent per month.

![]() , Published in numerous sites on the Internet,

, Published in numerous sites on the Internet,

February 1993

TrustMark 2001 by Timothy Wilken

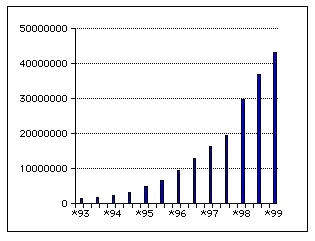

![]() shows that growth as estimated world wide web hosts from

shows that growth as estimated world wide web hosts from

January 1993 to January 1999.

![]() –

–

requirements necessary to establish a 'Knowing' Utility.

these revolutions– agricultural, industrial, communication, and

computer–occured? What is going on here? Where is our species headed?

Without any explicit plan to do so we have mastered agriculture, industry,

communication, and computation. Why?

systems. Our behavior is restricted by the principles of nature. Self-

TrustMark 2001 by Timothy Wilken

is an active phenomena, it is powerfully organizing always seeking efficiency

through complexity.

organizing themselves into evermore complex and interrelated systems. We

have a world travel system, world industrial system, world communication

system, and clearly a world economic system.

precedes the evolution of more complex life forms. We humans appear to be

following the same path that was taken many times by 'LIFE' in the past. This

was the path taken when molecular life organized itself into cellular life; when

cells became multi-cellular; when tissues became organs; and when organs

became organisms.

system? My body is a 'unified culture' of 40,000,000,000,000 cells operating

in harmony to produce the phenomena that I call 'me'. Is it our turn to

become cells in a new life form–the 'Unified Cultures of Earth'?

Gaia hypothesis– that the Earth is itself a living organism.

connectedness as to resemble an enormous embryo still in the

process of developing.”

Cultures of Earth' will operate more like a living organism then a political state. I

believe that the agricultural revolution, the industrial revolution, the communication

revolution, and the computation revolution represent the organizing nests of cells

that will form the organs for the new life form.

TrustMark 2001 by Timothy Wilken